You are hereBlogs / Steve Horn's blog / Interview: "Big Men" Director Rachel Boynton on Oil, Ghana and Capitalism

Interview: "Big Men" Director Rachel Boynton on Oil, Ghana and Capitalism

Cross-Posted from DeSmogBlog

The subtitle of the newly released documentary film Big Men is "everyone wants to be big" and to say the film covers a "big" topic is to put it mildly.

Executive produced by Brad Pitt and directed by Rachel Boynton, the film cuts to the heart of how the oil and gas industry works and pushes film-watchers to think about why that's the case. Ghana's burgeoning offshore fields — in particular, the Jubilee Field discovered in 2007 by Kosmos Energy — serve as the film's case study.

Image Credit: Ghana Oil Watch

Boynton worked on the film for more than half a decade, beginning the project in 2006 and completing it in 2013. During that time, the Canadian tar sands exploded, as did the U.S. hydraulic fracturing ("fracking") boom — meanwhile, halfway around the world, Ghana was having an offshore oil boom of its own.

Kosmos Energy (KOS), previously a privately held company, led the way. Adding intrigue to the film, Kosmos went public while Boynton was shooting. Kosmos didn't do it alone, though: the start-up capital to develop the Jubilee Field came from private equity firm goliaths Blackstone Group and Warburg Pincus, a major part of the documentary.

What makes Big Men stand above the rest is the access Boynton got to tell the story. Allowed into Kosmos' board room, the office of Blackstone Group, encampments of Nigerian militants and the office of the President of Ghana, the film has a surreal quality to it.

Now screening in Dallas, New York City and Portland, the film will soon open in theaters in Chicago, Seattle and Los Angeles.

After seeing the film at Madison's Wisconsin Film Festival, I reached out to Boynton to talk to her about Big Men, what it had in common with her previous film (one of my favorites) Our Brand is Crisis and what other documentary projects she has on the go.

Steve Horn: I've seen your first film, Our Brand is Crisis, and there seems to be a continuity in a way between Our Brand and Big Men because Bolivian ex-president "Goni" (Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada) was chased out of Bolivia eventually because he attempted to privatize Bolivia's gas and was basically in office to begin with because people from the outside came in and helped place him there (U.S. Democratic Party political consultants and electioneers) to begin with.

Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada; Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

One could see a similarity between the PR efforts led by those electioneers, which serves as the premise of Our Brand, and a western oil company like Kosmos coming into Ghana to bring offshore oil and gas drilling to the country.

Did what eventually happened in Bolivia with their gas market — because these U.S. consultants came in and helped get "Goni" elected —move you to start thinking about energy (oil, gas, etc.) as a documentary film topic?

Rachel Boynton: No, not at all. In that sense they're totally unrelated. The origin of both projects is completely unrelated.

I finished Our Brand is Crisis in 2005 and it had its theatrical run in 2006 and so back in 2005 I started thinking about what I wanted to do next and at the time, oil prices were going through the roof and everyone was freaking out about peak oil.

I was seeing it on the news constantly and I felt like I wasn't seeing inside of it. Here's the most important resource on the planet and everyone's talking about it, everyone seems scared and yet I'm not seeing anything from inside the industry.

I'm pretty good at getting access to things and so the original thought was that "You know, I want to do a story from inside the oil business, I want to get access to the inside of it." And then as I started looking at it — you know, the Gulf of Guinea is sort of this new frontier for oil exploration and it's considered under-explored territory — I thought, "Well that could be a good story."

.jpg)

Gulf of Guinea; Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

And then in late 2005 and early 2006, this militancy started in Nigeria started popping up in the news, with the militants attacking pipelines, kidnapping oil workers and causing worldwide oil prices to soar.

When I read about that I thought, "Well there has to be a movie there, right?" I mean, open conflict makes for good film. So, the original idea was to go to Nigeria and do the entire film there and that's how I began.

When I started, I didn't know anyone in the oil business and I didn't know anyone in Africa. I started by buying a plane ticket to Nigeria and that's how it began.

Horn: So, there's this kind of thread that runs through Big Men — it's not exactly the most prominent thing, but it's there the whole time — which is the capital investment behind Kosmos Energy and the firms Warburg Pincus and Blackstone. How did you come to make the decision and why did you decide to feature the private equity firms in your film?

Boynton: Well, it's a very important part of the story.

Horn: Right. Well, I guess what I'm getting at is often when oil and gas is talked about, the capital investment and private equity world/Wall Street world is not talked about. What was the reason why you chose to do so?

Boynton: Well, this is a different story than most. The work of a documentary filmmaker is difficult because you're doing a lot of competing things at once simultaneously.

First you pick your story. When you're following something over time, you ideally pick a situation in which you think there's going to be a story to tell, when you think something is going to happen.

You see it in a lot of films that are about let's say contests of one kind or another. "Our Brand is Crisis" is a kind of contest film. It's about a competition: who's going to be president. Inherent in that story is a sense of drama. You will have a winner and a loser.

"Our Brand is Crisis" Poster; Photo Credit: International Movie Database

The story of Kosmos Energy and Ghana was far more complicated than that because it was not a story about an open conflict or an open contest. It was a story about a discovery. And there was every possibility that things could've gone smoothly and there would've been no drama. And if that had been the case, then I would've made a very different film.

But that's not what happened. What happened was this enormous catfight, basically, over the money. Which some people might look at it and think that's predictable. I would certainly bet that when you're dealing with a massive resource worth millions and millions of dollars that conflict is sort of inevitable.

The choice of who's in the film and what the story is and how I portrayed the story, what facts to include or not to include, that has to do with me trying to distill what I want to emphasize in terms of the truth.

So to me this was really a story about capitalism and it's a story about self-interest and human nature. That's why it's called Big Men. For the purpose of the film, the equity guys are the biggest of the big men, so to not include them just wouldn't make sense.

Horn: Related to that, one of the questions I had was it seems like in the film the private equity firms are huge in — I wouldn't say pressuring — but at least raising the level of urgency on Kosmos to get deals cut with the Ghanaian government.

Would you say that was something you felt when interviewing the executives at Kosmos, that this was a real sense of urgency they felt because of pressure from the top of these two private equity firms?

Boynton: Yes. But I mean the pressure was multi-faceted. I mean there's pressure because they have to get the job done: they're trying to develop an oil field. And from their business perspective, their plan was to get the first oil as quickly as possible.

Kosmos had been conceived as a company that was going to sell its assets. Kosmos originally — it's a very different company today than it was when I began the film. When I began the film, they had no intention of becoming a publicly held company. They thought they were going to sell and that was sort of the business model: to discover the oil, to develop it, as they would say "to create value" and then to sell it; that was the plan.

So in order for that plan to work, they had to develop the field and ideally do it as quickly as possible because it's an enormously expensive endeavor to maintain an oil field. And once you get into start maintaining an oil field: you know Kosmos wasn't ExxonMobil. ExxonMobil has income from all over the world, so once ExxonMobil starts to decide to develop an oil field, they have plenty of other oil fields to pay for it with and Kosmos didn't have that.

ExxonMobil Headquarters; Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

One of the big pressures weighing on Kosmos' heads was they didn't have any source of income and then the financial crisis hit them.

So from the investor's perspective, they wanted to make their money back and they started to get really scared because here was the financial crisis, oil prices tanked and they knew they had up ahead of them these enormous expenditures. And so they knew financially — if you just looked at the numbers — it was a very scary situation for them.

Horn: Let's go back to what you talked about, you know, that at-large this is a film about capitalism. When you say that, what do you mean by that?

Boynton: Well, what did you think? You saw the movie, right? Do you see what I'm talking about?

Horn: (Laughs) Of course, yeah. That's why I asked the question about the private equity firms. I think it shows exactly how the global oil and gas industry works.

Boynton: I think this movie wasn't really about oil. The trick of this movie, the reason I think this movie is extraordinary, is that it works on many, many levels.

Unlike Our Brand is Crisis, which is a pretty simple film and a straight-forward story, it's one that's much, much easier to tell than Big Men and a lot less intricate with less moving parts. The two films do have a lot in common, just not what you were pointing to in your first question.

Big Men works as a story about Ghana and the story of oil there and the question of what's going to happen with Ghana. And that's sort of the most obvious, first level in which to look at the movie, a story of these places: Ghana and here's what went wrong in Nigeria and is it going to happen in Ghana? That's level number one.

Level number two, it's a story about people and the motivations that are driving them: a question about Ghana and self-interest is the same thing that's driving the human story, the individual story in the movie. The individuals are motivated and torn apart by self-interest in the same way that these countries are. So it works on this large level and also on a smaller level.

And it works as a story about — journalistically — telling the truth about something that happened. But I think it also works metaphorically: there are larger philosophical questions about human nature and how we want to live. To me, that's what makes the film interesting, these larger philosophical questions.

Horn: Would you say then in a sense that the stories of Ghana and Nigeria are just case studies of a much bigger question?

Boynton: I would never call them just case studies. I would say it's looking for a greater truth in a smaller story.

As I got into it and delved into it, I was very interested in the idea of wanting to be big. That's why the film's called Big Men. In the film, wanting to be big is about two things: it's about wanting to make a lot of money and it's about wanting to have a big reputation.

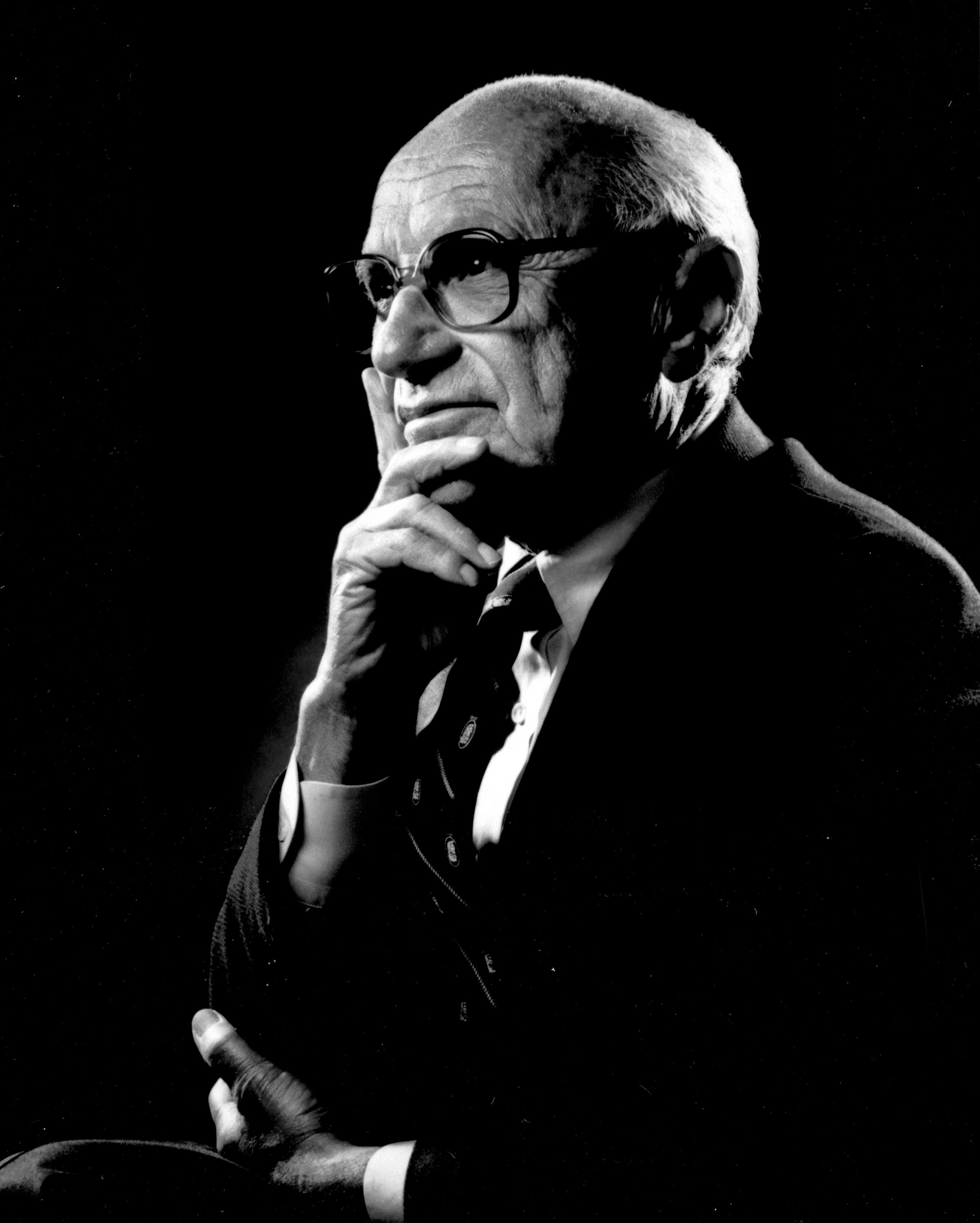

Those two things combined give you power and influence and freedom. And everybody in the film is going after those things and the film opens with a quote from Milton Friedman. Our entire worldview is organized right now around the pursuit of maximum individual profit, that's how the world's structured, that's the engine as Milton Friedman would say.

Milton Friedman; Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

But it's also the divider, but as one key character in the film says, "What unites us needs to be greater than what divides us." And that's much easier to say than it is to do, but it's the question and it's sort of one of the big questions the film is posing. How do you go about doing that and is it possible?

And certainly, it becomes more possible when you look at smaller concentric circles. Talking about a unified world might be impossible, but talking about a unified community or a unified nation might not be.

Horn: This question has come up before in other interviews you've done, but Brad Pitt was involved as executive producer for the film and my question is not so much about him but about how he also executive produced the film 12 Years a Slave recently and that was about Africa and what happened to the people of Africa because of slavery.

Did Pitt, in your talking to him, see any similarities or common themes between the two films?

Boynton: I can quote what he said, which is he's really interested in this theme of this notion of "what unites us needs to be greater than what divides us."

I mean, that is sort of a theme in "12 Years a Slave" and the idea of thinking about the reality of history and how people get treated and then moving beyond that into a new way of approaching things by confronting the reality. That's sort of in my opinion what "12 Years a Slave" was kind of about philosophically.

"12 Years a Slave" Poster; Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

But when Brad did the screening with me a couple weeks ago, he was talking about the film in terms of "responsible capitalism" and the idea, the hope really, that there is a way of doing things in which everyone can benefit. And he thinks that should be a goal, that should be something that we consciously make an effort to pursue, rather than this notion of maximum individual profit as the organizing principle.

Horn: So the last question for you is do you have any future projects in mind or things that you're working on?

Boynton: I do, I think I'm going to make a film about my husband, Steven Shainberg. At least that's what I'm thinking today. My husband's a fiction filmmaker and he's about to go make this crazy movie and I'm kind of fascinated by the process of it and by what he's doing. I think the movie's going to be great.

I think it could be really fun to make this film and I'm ready to do something that's really going to be fun.

Photo Credit: Getty Images

- Steve Horn's blog

- Login to post comments

-

- Email this page

- Printer-friendly version