You are herecontent / Joe Wright's "The Soloist" Exploits The Skid Row Community

Joe Wright's "The Soloist" Exploits The Skid Row Community

Two Fridays ago on the first day of its release, I went to an early afternoon screening of the film The Soloist. I'd been eager to see it since it focuses on the real life relationship between Los Angeles Times journalist Steve Lopez and Nathaniel Anthony Ayers, a homeless member of Los Angeles' Skid Row community suffering from debilitating mental illness. In the story, as told in Lopez' columns in the LA Times, in his book, and in the screenplay by Susannah Grant, Lopez first meets middle-aged Nathaniel Ayers in downtown Los Angeles in front of a statue of Beethoven where Ayers is playing a two string violin. In that serendipitous meeting Lopez discovers that as a youth Ayers had been a gifted student at Juilliard, New York's prestigious school for the performing arts. This revelation leads Lopez on a personal mission to rehabilitate the troubled man - a mission Lopez is still on today, four years after their first encounter.

My intense desire to see this film had been predicated, foolishly as I have since come to learn, on the romantic notion that viewers would see The Soloist and be moved to help the homeless. But the film I saw, with its cartoon-like unsympathetic portrayal of the people of Skid Row, that displayed none of their individuality, humanity or humor, would never provoke such action. Instead of showing the hearts of the inhabitants and telling a few of their tales, the film portrayed them as a Fellini-esque monolith - a tainted Gomorrah teeming with decadence and dereliction.

It would be hard to imagine that anyone seeing The Soloist's unabated lawlessness and out of control crowds could be moved to set foot on Skid Row, having been made to believe that all that awaits them is danger. Anyone, that is, except me, who became so enraged by the exploitive portrayal of the Skid Row inhabitants that I phoned my friend, Jamie Romano, a longtime advocate for the residents of Skid Row, and asked her to meet me right away for a walk along The Nickel - the local term for the area along 5th Street which runs the length of Skid Row. Jamie instantly obliged with an emphatic, You got it!

I drove straight downtown from the West San Fernando Valley and picked Jamie up on the corner of 6th and Broadway. We parked and walked the length and breadth of the community in search of the legions of lawless portrayed in the film. They were no where to be found on that day, or the next day when I returned to continue my search. What I uncovered instead is a malaise more perverse than Mr. Wright's orgiastic assault on the poor and the mentally ill. What I uncovered is the gentrification and police mobilization of downtown Los Angeles designed to wipe the streets clean of the defenseless to pave the way for the well-to-do.

As shared with me by Steve Diaz of the civil rights advocacy group Los Angeles Community Action Network (LA CAN):

The depiction of the [Skid Row] community in the The Soloist is very fictional. I've been downtown for over 7 1/2 years either living or working in the community. During that time I've never seen the amount of lawlessness that's shown in this movie. It [the lawlessness] validates the perceptions that the business community is using to advance the criminalization of poverty. As to the number of people on the street outside LAMP - you could walk down San Julian Street [where LAMP Community is located] now or in 2005 or 2006 when the film depicts Lopez' visiting Nathaniel Ayers and never see that many people. The perceptions advanced by Steve Lopez' [LA Times] articles were the basis to validate the increased police presence. Only a few months after Lopez' last article, the Safer City Initiative was launched.

The Safer City Initiative (SCI) referred to by Diaz is considered by Skid Row advocates to criminalize poverty. It institutes regulations that make it nearly impossible for the poor to live lawfully on the streets of Los Angeles. Included in the legislation are laws that outlaw sitting or lying on the sidewalk between the hours of 6AM and 9PM, and a rigorous enforcement of jaywalking regulations that wield hefty fines. SCI designates that Skid Row residents can ONLY sit or sleep on the sidewalk between the hours of 9PM and 6AM or else they will be cited. The fines for breaking these laws are impossible for the poor and homeless to pay. As a result, their unpaid tickets go to warrant and the warrant results in arrest and imprisonment. It's an endless cycle of citation and incarceration designed to reduce the number of homeless in Los Angeles and pave the way for rapid gentrification.

Elaborate downtown reconstruction has already been completed and more is underway to usher the upper class and wealthy into expensive renovated lofts and send the homeless packing from the one square mile of Los Angeles that was designated to serve them. In the 1970's, under a policy known as "containment," Los Angeles purposely concentrated its homeless services into this one tiny area. And now, as the wealthy move into their lofts, the homeless are disappearing at alarming rates. Jamie Romano is furious by the unjust consequences of this legislation. She characterizes it as a sinister plot and tells me with unflinching candor:

The Skid Row population is predominantly black. Removing a race of people from their home by whatever means amounts to ethnic cleansing.

New renovation of downtown Los Angeles (Photo by Linda Milazzo)

New renovation of downtown Los Angeles (Photo by Linda Milazzo)  New construction in downtown L.A. Homeless people right below it. (Photo by Linda Milazzo)

New construction in downtown L.A. Homeless people right below it. (Photo by Linda Milazzo)

To Steve Lopez' credit, he's voiced strong concern over the Safer City Initiative. As he recently told me:

The fact that there are fewer people there [on Skid Row] today doesn't necessarily mean we did all the right things public policy wise. A lot of people have been shooed and scattered to other areas. There has been quite a bit of permanent supportive housing put in place since the whole story began... We've got a long way to go. A lot of people have argued that they were a little too heavy handed with the police action and too many people who didn't pay the last jaywalking ticket now end up in jail or prison and it's no surprise to anybody that 2,000 people in the LA County Jail and between 20 and 30% of the nation's prisons are people dealing with mental illness. You know of course that there are better ways to deal with them.

In truth, I wasn't expecting a white-washed or sanitized view of Skid Row homelessness, mental illness, poverty and drug addiction in this movie. But I have personally witnessed the humanity on Skid Row. And so has my friend, Jamie, who tells me deep with emotion:

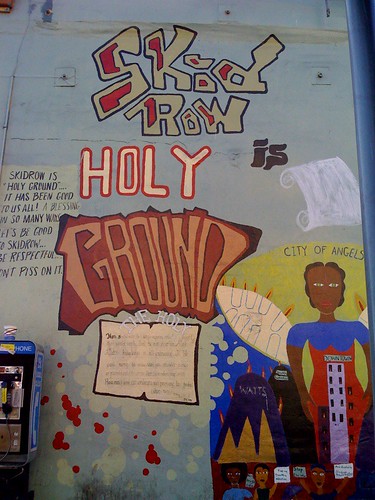

I've been working among the people of Skid Row for over 7 years. My experience with the Skid Row community has consistently been moving and inspiring. In the midst of sickness and despair is a loving, familial community of people who care for, protect, and provide for each other. It's a place where people are humble with gratitude. Countless times I've been kissed, hugged and blessed for something as simple as providing a pair of socks or a bottle of water. Skid Row is absolutely holy ground.

For the record, I'm no stranger to Skid Row. But unlike Jamie, who traverses the area regularly, I continue to visit periodically as I have since 1974 when I became a community organizer with the Greater Los Angeles Community Action Agency (GLACAA), the nation's second largest anti-poverty program which bestowed upon me at age 25, the absurdly long title of Volunteer and Resource Development Specialist.

My office at GLACAA bordered Skid Row at 6th and Hill. Each morning I parked my car at the Greyhound Bus Terminal on Skid Row, returning to it often during the day and frequently into the night, passing homeless folks along the street. I was on a first name basis with many and lent a few dollars whenever I could. They were friendly and gracious. Some suffered varying levels of mental illness, alcoholism and drug addiction. Some had simply fallen on hard times. They were unkempt and pungent. Some walked me to my car parked on the darkened roof of the Greyhound Station when I worked into the night. They were never antagonistic or aggressive and they often made me smile. They were folks - as was I.

In the following decade, 1988 to be exact, I volunteered with the great organization, Frontline Foundation, to deliver lunch by van to homeless encampments throughout downtown Los Angeles, which included the streets and alleys of Skid Row and outlying areas along the train tracks where communities of people lived. It was the heyday of crack cocaine and its ravages were shocking. The poverty was overwhelming. AIDS was wreaking havoc and claiming lives, and the disenfranchised stricken people who accepted Frontline's food did so with gratitude and humility.

At the end of the next decade, the 90's, and into the new millennium, I was Program Director of a joint venture between the City of L.A. and the adult division of the Los Angeles Unified School District for which I placed educational programs in Community Based Organizations; some along Skid Row. Drugs, mental illness, alcoholism and hard luck were still the qualifiers that populated Skid Row - yet as had always been my experience, the residents were engaging and familial as they battled their many demons. I never feared them. I simply feared for them.

It was this thirty years of mingling with and experiencing the folks on Skid Row that so appalled me as I watched them portrayed in raging crowd scenes as lawless and incoherent by The Soloist's British director, Joe Wright - who in my opinion was an odd choice to helm this film. Rather than expose their humanity, Wright, whose previous works include period pieces "Pride and Prejudice" and "Atonement," focused on the harshest aspects of their personae, rendering them unsympathetic and cartoon-like. Countering my claim that Wright was a poor choice, Steve Lopez told me he believed Wright was the right choice because he stayed fully invested when making the film. According to Lopez and others close to the project, Wright, at first, didn't want to do the film. But he came to Los Angeles and spent ten days with the people on Skid Row. He then went forward with the film.

Somehow I'm expected to believe that in the ten days Britisher Wright languished on Skid Row he miraculously "got" the community, absorbed its nuanced layers, and understood mental illness and poverty well enough to honestly portray the 500 residents he hired on as extras. If that were true, why then did Wright encourage the over-the-top behaviors that further exploited the residents? Was it simply to mirror his idol, Federico Fellini, by creating outlandish imitations of real people?

Director Wright committed a major injustice against the Skid Row community by creating a monolith of inhumanity which he melded them into. Throngs and throngs of drug crazed, illness crazed, violence crazed people who rarely displayed a single lucid moment. Rather than pay respect to their suffering, Wright placed them in a cinematic stupor and filmed them in a Fellini-esque haze. But where Fellini created cartoons from actors he hired to play cartoons, Wright created cartoons from people he hired to play themselves. Lest anyone doubt Joe Wright's fidelity to Fellini, here's Wright in a London interview discussing the iconic director:

I also think a lot of literary people presume that literature and the written word have a monopoly over internal truth and I personally, as a dyslexic, don't agree with that. I think, to me, the films of Fellini or Bergman or the great classical masters of the medium spoke just as much truth as Tolstoy or Dickens.

Wright's philosophy that cinema is the purveyor of truth, wholly equal to its literary model, was welcomed by Steve Lopez who authorized Wright to make any cinematic alterations to his book that Wright desired. Of course those who know Hollywood understand that writers must abdicate control of their work to studios and directors. Thus Lopez had little choice. Still, as Lopez told me:

I'm often surprised at how many people expect a book to be like a movie. I thought that in this movie they made all the right moves and pushed all the right buttons.

Those moves Lopez refers to were clear deviations from his book. When I asked Lopez if the crowd scenes in the movie on San Julian Street outside the Lamp Community were as populated, lawless and frenetic as when he actually visited Nathaniel, Lopez admitted the film did take liberties with those scenes, as it also did by depicting Lopez as divorced, living alone, when in reality he lives with his wife and daughter. Lopez explained:

There's no reason for an artistic contribution to be exactly like a piece of art that already exists.

Lopez asked if I accepted that philosophy and I told him I believed the quality test for a film based on a book is how closely the film resembles the book. I used the immensely popular Harry Potter series as the example where film goers would be gravely disappointed if the films deviated from the content of the books. Lopez stated this wasn't as critical for his book since his was read by just 100,000 people. Still those 100,000 readers who view the film might be disappointed if the test for mirroring the original isn't met.

But Wright's artistic license sacrificed more than a couple of facts. It sacrificed an entire community of already disadvantaged people to provide Wright's preferred backdrop of rampant drugs, violence and derangement. In a town Steve Lopez contends is driven by the individual:

A lot of people believe this is a real community but it's more about the individual

Joe Wright fully ignored the individual to create a monolith with no singularity or depth. Yet all around the Lamp Community (Nathaniel's service provider in fact and film), and up and down Skid Row, countless acts of kindness are carried out each day. Allow me to introduce you to CJ, who Jamie and I encountered just by walking along the street.  (Photo by Linda Milazzo)

(Photo by Linda Milazzo)

CJ spends what little money she has to care for a community of cats living behind the gates of San Julian Park - a park the Safer City Initiative has shut CJ and her community out of.

Tell me, Joe Wright, where are the CJ's in your movie?

I understand Nathaniel Ayers was the focus of your film. And your film, like all films, is constrained by time and budget. But surely, two minutes cut from an unruly crowd scene could have lit the way for CJ, or someone like CJ, who doesn't shy away from cameras. CJ regularly visits San Julian park just down the street from Lamp Community - a principal venue for your film.

I've heard from Steve Lopez, The Soloist's co-producer Gary Foster and its music advisor, Ben Hong, who appeared together on a panel at UCLA, that making this film was transformational and the experience changed them forever. Gary Foster says he still maintains relationships with some of the folks he met, including a woman named Detroit who calls his office nearly every day. Lopez told me directly that Joe Wright, who I didn't get to interview for this piece, was also profoundly affected by the folks on Skid Row. But for all his supposed deeply felt connection, Wright was either unable to, or disinclined to translate the residents' individuality, humanity, and sense of community to his film.

Two days ago I had a discussion with Casey Huran, Executive Director of Lamp Community, about what life is like on Skid Row. Casey told me the following:

There are tens of thousands of Nathaniels who have extraordinary contributions, gifts and talents who have been marginalized from our mainstream society at our great loss. There's a peacefulness, a joy, a camaraderie that's almost an enigma. When you're talking to people you feel their joy. It rubs off on you. People are so kind. I've traveled the world and have never seen the level of community I've found here.

Tell me, Joe Wright, where is this Skid Row in your movie?

Collaborating on this article: Jamie Romano, Advocate for the Skid Row Community

- Login to post comments

-

- Email this page

- Printer-friendly version